Stoicism or self-care?

An examination of psychological resilience.

In a western world experiencing a radical increase in mental health issues, the question of psychological resilience, and its counterpoint, psychological fragility, has become paramount. The answers being suggested by the psychological community range from the stoic cognitive approaches, and mindfulness, to the self-esteem focused ‘self-care’, and active relaxation strategies. While none of the above fully address the problems seen in our rapidly collapsing society, it is clear that psychological resilience and how to improve it, is an issue of great importance.

A question puzzling to students of history is why mental health problems such as anxiety and depression, and their symptoms, self-harm and suicidality, have risen in young people since 2011? On face value, it would seem that living in a time and a place that has virtually eradicated extreme poverty, has the benefits of nationalised, and effective healthcare and education, with welfare available to all and having largely eliminated violent crime, would be beneficial to one’s mental health. Evidence to the contrary suggests that there must be more at play than the simple equation of physical safety plus the means to live a fairly substantial life equalling good mental well-being.

In a wide reaching essay, Carl Trueman diagnoses the modern mental health affliction as one stemming from the burden of psychological identity being thrust upon the western individual; he suggests that in prior historical periods, the family unit, religious belief, and a national (or community) connection provided a fairly complete identity to the individual. Trueman proposes that previously the individual measured their efficacy against the expectations placed on them by their family, the church and the state, never having to come up with the standards themselves, with this alleviating much of the anxiety that modern individuals have in having to ‘discover’ who they are. While his essay provides an account of why the emphasis on psychology over community has created a range of issues for the average person to deal with, the recent increases in mental health issues amongst young people are unprecedented, considering the focus on psychological identity has been prominent for much of the last century.

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, in their 2018 book The Coddling of the American Mind, lay the blame for this increase squarely at the feet of social media. Since the advent and subsequent ubiquitous usage of smartphones and the rise of Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok as primary methods of communication amongst young people, the problems highlighted by Trueman have become exacerbated. While previous psychologically driven generations have only had to reckon with the development of their own psychological identity, young millennials and Generation Z have had to simultaneously develop their identity while also contending with the constant comparison to their peers that an always connected online persona brings.

All this begs the question of how we can improve people’s psychological resilience, so that they are better able to cope with the difficulties of having to develop a psychological identity and also navigate an interconnected world which seems to be doing its best to erode resilience in the individual.

In a wide reaching summary of the research on psychological resilience Marc Zimmerman lays out the evidence for three different types of psychological resilience, defined as someones ‘ability to bounce back’ after experiencing a psychological hardship. Each of these, detailed below, are dependent upon close community support of the individual.

The first type is compensatory resilience — this is defined as factors which counteract the detrimental mental health effects experienced by the individual. For example, a child who is bullied by his peers at school relies on the close relationships he has with his siblings, preventing him from suffering severe psychological damage in the way he relates to others. It does not prevent him from suffering harm, instead it provides a counterpoint which can be relied upon to compensate for any pain inflicted.

The second type is insulatory resilience (or the ‘protective factors model’) — defined as resilience that utilises ones relationships with close family and trusted members of the close community in order to shield oneself from the full impact of the hardship experienced. An example he uses is the moderation of self-worth that occurs in young native American mothers who have close older females around them, protects them from post-natal mental health difficulties. They are insulated from the mental health difficulties, which are better absorbed into the community through relationships which enable the young mother to overcome feelings of inadequacy. This is different from the compensatory model in that the protective factors prevent the psychological damage from ever occurring to the individual, whereas in the compensatory model, while damage occurs it is counteracted by an individual’s positive relationships.

The third type is inoculatory resilience (or the challenge model) — this theorises that mild or moderate exposure to risk and harm, within a safe context, can enable an individual to develop strategies to help them cope with future difficulties. It is important to note that the risks have to be sufficiently challenging, while remaining free of the risk that they do long term damage to the individual. An example would be the challenge by one’s father to mow the lawn every Saturday morning before being allowed to play. This provides a young person with a relatively challenging and difficult task, which helps them learn how to overcome boredom and exhaustion, while also being taught to the young person in a safe context.

It is interesting to note that each of these three models rely on a supportive community being present around the individual in order for them to work. It is clear that with recent social trends towards single parent households, with community cohesion deteriorating and religious communities dissolving, that individuals in the west often find themselves having to develop coping strategies, rather than being enabled and encouraged to develop psychological resilience within a loving family or community context.

In response to the disturbing drop in perceived psychological resilience and increase in efforts to find coping strategies that might work, a cottage industry in self-help focusing on mindfulness and stoicism has arisen. Cynically, the critique that can be laid against these approaches to mental well-being are that they put the onus for change on the individual. It is all well and good for a corporate entity to provide their employees with workshops in mindfulness meditation, but when the problems in workforce moral come from a focus on the abstract, and a preoccupation with the short-term success that sociopathic corporate leadership brings, then the individual who finds no solace in his timed breathing exercises is left stranded.

Other oft cited self-applied remedies for the dramatic rise in mental health issues seen in the west is the adoption of ‘resilience strategies’ that focus primarily on relaxation and boosting one’s self-esteem through positive self-talk and through seeking encouragement from others that one is alright in who they are. In many cases this can mean taking time out to do something that one enjoys, getting away from the problem, and spending time consuming.

This is a problem for many, as recommendations for individuals to spend time working on their self esteem and looking after themselves by doing things that they enjoy, ignores the fact that people rarely pursue activities that are intended to psychologically strengthen themselves.

The disproportionate focus on bringing up ‘self-esteem’ ignores the value of developing one’s character in order to become more virtuous. It would be better for an individual who feels worthless to instead work on improving their contributions to the community, thereby developing the level of ‘esteem’ that one has within the group.

As many people have experienced, through working underneath a sociopathic boss, or dating a shallow narcissist, a person can have a high level of self esteem coupled with a low character. However, it is very difficult for a person with a strong, community oriented character to have a low level of esteem within that group. Recognition of the relationship between quality of character and esteem is extremely valuable, but overlooked in mental health literature, in favour of ‘self-esteem’ as the primary measure of self-efficacy.

When a selfish narcissist is asked about their self-esteem, how will they respond? Of course they will have a high regard for themselves and their impact on people around them, however, this does not make them a noble individual. If you contrast this with the response that one who has a high level of civic virtue would give, they will likely identify areas in their lives where improvement could be made.

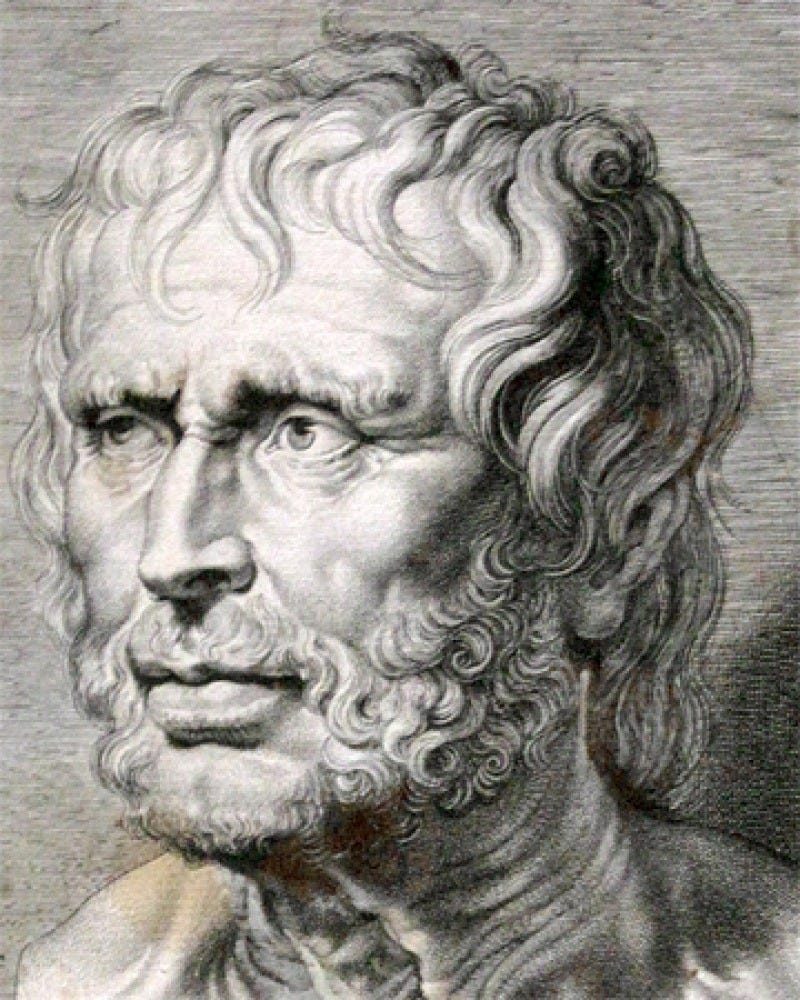

Seneca the Younger — one of the fathers of stoic philosophy, wrote of four virtue that one must develop in order to be an effective individual. These were patience, resilience, moderation and courage. All of these are only capable of being developed by taking a difficult path; if one does not embark on his practise of these virtues in his daily struggles, when the hard road is eventually taken, they will not be sufficiently developed, and it will break him. It will also be impossible for the one who has too high a level of self-esteem to ever recognise that he needs to begin the process of self-improvement in these areas.

This identification of the need to build character is not a negative, but we mistakenly devalue this as an indicator of positive mental health. It is clear however, that someone who has a high level of insight into their developmental needs is one who is on a path towards self-actualisation. Focusing instead on a high level of self esteem, which has very little correlation with the quality of that person’s relationships with others, or their recognition that they have to contribute to avoid disruption to community cohesion, leads us to infantilise individuals who have a responsibility to change aspects of their character — to develop virtues and to resist vices.

Often the answer to mental health issues is not to ‘feel better’ about oneself, but it is to examine one’s actions and to adopt the stoic responsibility of doing one’s best to improve the things that are in one’s control. The trend towards improving self-esteem can lead many to take the path of least resistance in their choices. While this can alleviate anxiety or depression in the short term, this is not the road to a satisfying or fulfilling life.

The preeminence of the self-care and self-esteem methods for managing mental health have led to a damaging feedback loop, whereby the opportunity to change is missed, and the existential anxiety avoided instead of confronted. This is done in favour of a ‘safer’ option which alleviates in the short term, but exacerbates the problem in the long run, when one is once again presented by his broken mental state with an opportunity to change and grow. Without having practised taking the hard road, one is left unprepared for when the hard road is the only one left to them.

Marcus Aurelius, whose meditations comprise the most widely read literature of the stoic corpus, lays out three enabling disciplines as an antidote to the terror of life. These are, the discipline of assent — being that our judgements or appraisals of our situation are our only source of freedom, the discipline of desire — focusing on the insignificance of our lives and the fragility of our existence and embracing our fate, and the discipline of action — that is, looking out for how we can serve the community and asking ourselves what is the greatest common good that can come of my current action? By utilising our judgements, focusing on what we can control and limiting ourselves to that which would benefit the community, Aurelius suggests that we become the master of the natural world as it presents itself to us, and as powerful as we can possibly be, in the circumstances we find ourselves in.

Similarly Martin Seligman, who first developed the ‘positive psychology’ movement, identified five elements of a satisfying life. Positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement (PERMA). While his PERMA model was primarily diagnostic, it is interesting to note that of his five factors, only meaning could be present in all possible life circumstances. Seligman correctly identifies that in order to be able to live through hardship, one must ascribe meaning to the suffering one endures. The stoics suggested that this meaning was the development of psychological strength and endurance, that by taking a hard path, one would become strong enough to take further paths in future, and by adopting Aurelius’ discipline of assent, our judgement of situations out of our control could enable us to face them head on, with courage.

It is clear that in order to address one’s own fear and pessimism, looking ahead to what one can do to change, one should adopt an attitude towards their daily lives such as examining the choices before one and choosing the hardest virtuous thing possible that can be done well in every case.

Though the issue of psychological resilience is a bleak one given community breakdown and the prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders, it is clear that the only way forward for individuals who want to improve is to reject the shallow coping strategies that alleviate the discomfort of circumstance, and to embrace the challenge of picking up the pieces. Choosing the hard, virtuous road is not one which is painless, but perhaps, if one is very fortunate, it could be the avenue to one’s emancipation.